How do new behaviors and morphologies evolve? Which genes are involved, and what kinds of mutations are responsible for causing one species to look and behave differently than another?

These are the questions that motivate me as an evolutionary geneticist. I study flies in the genus Drosophila. Flies are really the perfect animal to study how behavior and morphology evolve. They’re easy to breed in the lab, they’re fantastically diverse, and they’re amenable to genetic dissection.

The species I work on are Drosophila elegans and Drosophila gunungcola. These species are unique in that they have very different patterns of courtship behavior and morphology while still being interfertile in the lab. That means they can still breed to make hybrids.

Male D. elegans perform a variety of activities during courtship, including chasing, circling, shaking, and wing display behavior.

Drosophila gunungcola courtship

For the most part, male. D. gunungcola only perform chasing behavior during courtship before attempting to mount and copulate with the female.

Watch Drosophila elegans/gunungcola hybrid courtship

Drosophila elegans/gunungcola hybrid courtship — Interestingly, D. elegans/D.gunungcola male hybrids perform courtship patterns that resemble a mixture of both parental species.

Phylogeny of Drosophila species

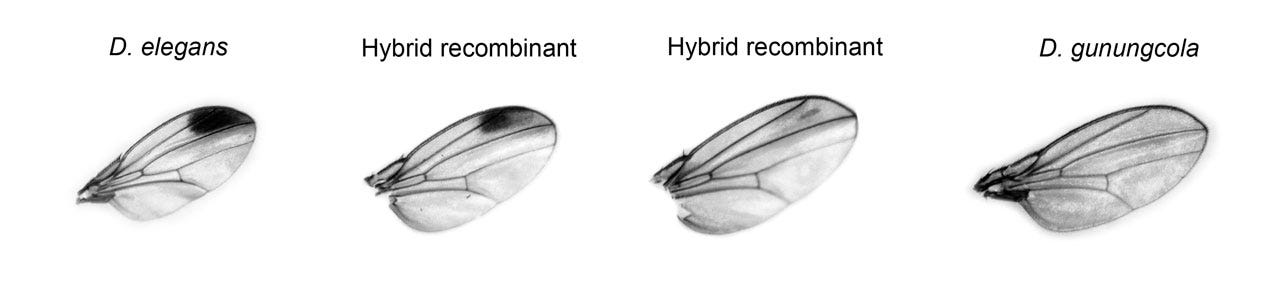

D. elegans males possess dark wing spots that they display during courtship by extending their wings out to the side and shaking back and forth in front of the female. Male D. gunungcola have a far simpler courtship pattern, and their wings lack any spot.

A male fruit fly D. elegans courts a female by displaying its wings

By crossing these species together in the lab, I have made hybrids that possess different amounts of each species genome. These hybrids allow me to genetically dissect which genomic regions are important in causing one species to have spots and wing display behavior while the other lacks both traits.

Wing Spot Variation Figure illustrates the ranges of wing spot diversity that we see in hybrid recombinants

Hybrids not only have variable amounts of pigmentation in their wings, but also perform wing display behavior that looks like a mix between both species.

Hybrid Courtship. This male has “trouble” performing the courtship ritual as illustrated by his strange looking wing display.

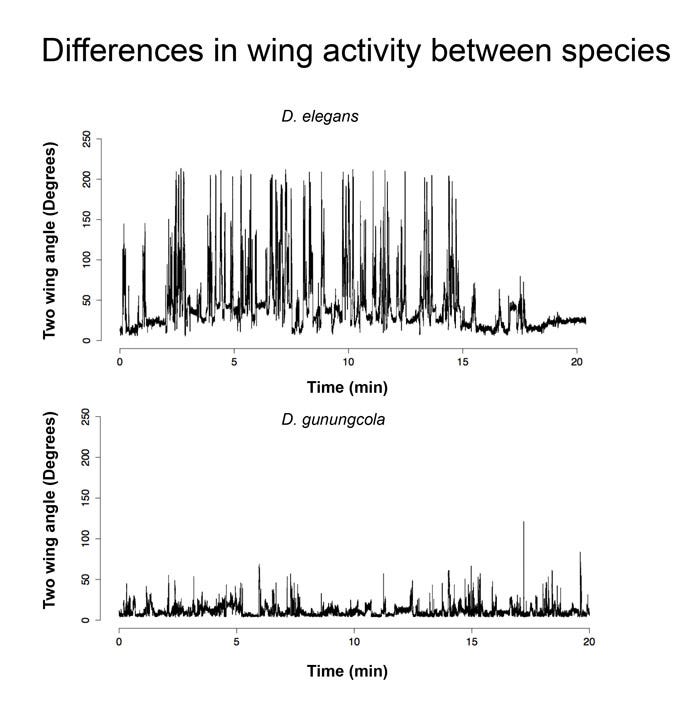

To genetically dissect how courtship behavior changes in hybrids, I am applying new computer tracking technology developed by Eyrún Eyjólfsdóttir and colleagues at the California Institute of Technology. The body, leg, and wing position of multiple flies can be quantified throughout courtship, which gives me tons of data to analyze.

“Sample readout of how we’re using the tracking technology to measure the behavior.

The Caltech FlyTracker aims to track the pose (position, orientation, size, wing- and leg positions) of multiple flies and maintain their identities throughout a video. In addition to trajectories, it outputs features (such as velocity, facing angle to other fly, and wing angles) useful for behavior analysis.

The figure below is just one example comparing each species courtship behavior. Each graph illustrates variation in the wing angles made between each wing tip for a single male during 20 minutes of courtship. The giant peaks in the D. elegans plot correspond to the wing display photographed above.

About the Author

Jon Massey is a PhD Candidate in Dr. Patricia Wittkopp’s laboratory at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His research focuses on understanding how changes in genes and development cause species differences in behavior and morphology. In his free time, Jon likes to keep bees and harvest honey to share with friends.