I am an artist who is fascinated by animal behavior, parasites, psychology experiments, and the biology of reproduction before cell theory.

My work mines the “cultural unconscious” of science — the imaginative, playful, spectacular, and bizarre — as well as the political: those aspects which are repressed when we consider science as objective, dispassionate, and without bias.

The language of video enables me to decode scientific evidence — its diagrams, illustrations, data, specimen, and instruments — and recode its stories as art.

In this postmodern playpen, I combine documentary fact with fiction, politics with biology, narrative with critical analysis. Experimental film and video art provide a medium and a pretext for my so-called research.

Primate Cinema: Apes as Family

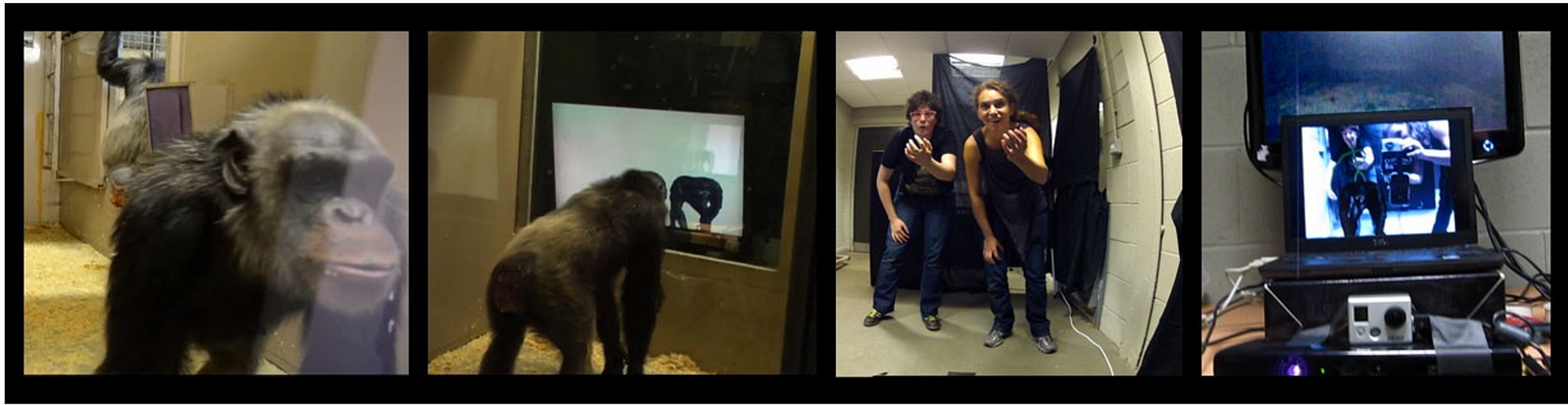

Primate Cinema: Apes as Family is a drama made expressly for chimpanzees — and the chimps reaction to its screening at the Edinburgh Zoo. Chimpanzees watch television as a form of enrichment in captivity. But no filmmaker had made a film for a specifically ape audience.

Commissioned by Arts Catalyst, and supported with an art-science grant from the Wellcome Trust, the director, in consultation with primatologists, researched chimpanzees’ reactions to a variety of television genres — Teletubbies, wildlife films, human actors playing chimp behavior, kettle drums, chimpanzee display behavior.

Chimps’ seem to like to watch the same things as human primates — dramas around food, territory, social status, and sex. In Apes as Family, the protagonist is a young female chimp, played by a human in an animatronic costume, whose facial expressions are controlled by puppeteers.

The young female, like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, encounters strange males on an adventure, which eventually leads back home. The drama is intercut with the chimps’ responses to the film, when it premiered at the zoo.

Chimps were attentive to the film; some sat and watched, others attempted to touch or smell the characters, and other appeared to mimic the action on screen.

The project was intended to create a prism for human beings to think about the inner world of chimpanzees. By watching a movie through chimps’ eyes, we can imagine what they think and feel. Chimps are, after all, our closest relatives. Known for their complex social, cognitive and emotional lives, they also share with us a fascination with cinema.

The film was first presented as a 22 minute two channel video installation, with the drama for chimps on one side and documentation of the chimps watching on the other. Edinburgh Visual Art Festival, Scotland. photo by the artist.

The Making of Primate Cinema: Apes as Family

This documentary shows director Rachel Mayeri working with comparative psychology Dr. Sarah-Jane Vick at the Edinburgh Zoo doing research with chimpanzees on their video preferences, and working with actors in chimp suits to produce films for chimpanzees.

Chimps and Humans Play Interspecies Video GameChimps at the Edinburgh Zoo are responding to on-screen chimp avatars whose movements are controlled through the actions of two human actors in the room next door. The two screens show two simultaneous views of the chimps in a voluntary research pod, front and back.

The ape avatar was in development, and although it was spastic, two chimps appear to play with the screen and with each other.

Primate Cinema: How to Act like an Animal

In the video, “How to Act like an Animal,” workshop participants in Los Angeles reenact a clip from a wildlife documentary. The clip depicts chimpanzees hunting a red colobus monkey and then eating the meat. The clip is excerpted from the 1995 National Geographic documentary The New Chimpanzees that was shot at Jane Goodall’s research site in Gombe, Tanzania, and features the community she researched for over thirty years.

In the video, the documentary sequence plays through three times on one channel, while the performers are seen acting in real time in relation to the footage on a second channel. The first loop shows the workshop actors watching the monitor showing the clip. The second time through, the actors have been directed to simply “act like the chimpanzees.” In the third instance, actors are assigned roles of individual chimps, and the video is edited shot by shot.

Primate Cinema: Movies for Monkeys

Incredibly short and slightly pornographic films to appeal to squirrel monkeys, who have an attention span of two seconds.

Primate Cinema: Baboons as Friends

Primate Cinema is a series of video experiments that translate primate social dramas for human audiences.

The first experiment, Baboons as Friends, is a two channel video installation juxtaposing field footage of baboons with a reenactment by human actors, shot in film noir style. A tale of lust, jealousy, sex, and violence transpires simultaneously in human and nonhuman worlds.

Beastly males, instinctively attracted to a femme fatale, fight to win her, but most are doomed to fail. The story of sexual selection is presented across species, the dark genre of film noir re-mapping the savannah to the urban jungle. Created in collaboration with cognitive scientist, Deborah Forster, who shot the field footage of olive baboons in Kenya.

Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii

A 29-screen video installation examines The Life Cycle of Toxoplasma Gondii and the memetic proliferation of cat videos. T. gondii is a parasite spread by cats, which is present in 30% of the human population.

The microbe reproduces in cats, and is spread fecal-orally. When imbibed by other animals, the parasite produces cysts in muscles, even the eyes and brain. Mice and rats with toxoplasmosis lose their innate fear of cats, and are instead aroused by the smell of their urine, causing a “fatal attraction.” The cats can capture and eat these docile rodents, and thus the parasite completes its life cycle — through mind control.

Image of installation. Courtesy of Pitzer College Art Galleries, Pitzer College, Claremont, California. Photos by Robert Wedemeyer.

While generally presumed to have no effect on healthy people, recent studies by Czech evolutionary biologist, Jaroslav Flegr, show that those who carry the parasite exhibit personality changes, which increase over time. This may be due to neurotransmitter-producing enzymes in the cyst, which sometimes lodges in the brain.

Women become more easy-going, gregarious, and attentive to dress. Men become more jealous, suspicious, and sloppily attired. Toxo-infected people have slower reactions times, leading to greater probability of car accidents. Toxoplasma is commonly found in schizophrenics, and may cause more severe hallucinations and delusions.

Human beings are apparently a dead-end for the parasite, which does not return to the cat to sexually reproduce, as it can with prey.

However, the proliferation of cats as pets — and on the internet as videos — might suggest otherwise. The installation explores the relationship between our biological affinity for cats and the technocultural expression of that desire.

Primatologist Patricia Wright as ring tailed lemur, test for “The Jollies”

This is a biographical artwork about the late primate scientist/conservationist/Alison Jolly, which gave me an opportunity to talk to and about the first generation of women primatologists. It was commissioned for a show in Australia called Femel Fissions.

For the exhibition, a group of women artists were asked to make artworks “inspired by a historical woman scientist.” I interviewed Jolly’s colleagues as well as Donna Haraway, animated their faces and voices to different animal characters, and made a four channel video installation; two pairs face each other as if in conversation.

In the exhibition space, there is wall text explaining who the interviewees are, and more information about Alison Jolly.

The primatologist Alison Jolly (1937–2014) was known for her pioneering theory on the evolution of social intelligence developed through her study of ring-tailed lemurs. Her scientific and conservation work drew worldwide attention to the unique ecosystem of Madagascar.

In this biographical artwork, the artist presents interviews with Jolly’s network of colleagues, friends, and family. Many voices articulate the significance of her scientific discoveries as well as her career: group living over tool making as a driver for evolution, her description of a female dominant primate society, the role of play in learning, as well as her place in the first generation of women in the field of primatology and her development of community-based conservation.

Monkeys, lemurs, and other nonhuman characters animate the conversation, producing reflection about humans as part of the primate order, social network, and ecosystem.

All films in the Primate Cinema series are distributed by Video Data Bank